Why the West Excommunicated Nature

The Arc of Western Ideology from Animism to Worshipping the Intellect

One of the defining characteristics of humanity is how diverse we are as a species. Depending on where you are on Earth, homo sapiens can look and sound very differently and believe very different things. These beliefs germinate into culture. As Wade Davis surmises: “every culture is a unique answer to a fundamental question: what does it mean to be human and alive?” (Davis, 2009, p. 20). Ultimately, these answers are based upon belief.

Over the last few hundred years, we have seen the rise of the industrial capitalist approach to living, which has enabled preternatural leaps in quality of life and population growth for humans. However, it also paved the way to massive extraction of natural resources well beyond the carrying capacity of the planet, pushed ecosystems to the brink of collapse, and corresponded to a massive extinction in our own species’ cultural diversity.

What beliefs power an industrial capitalist culture that sanctions rampant over-exploitation of the natural world?

The development of industrial capitalist ideology fundamentally re-organized the cosmic hierarchy and humanity’s place in it. Over the last 3,000 years, we shifted from a mythic tradition based on the essential unity of humanity, nature, and God to an empirical tradition based on humanity’s supremacy in the material world. From belief in reverence, respect, and unity with nature, the West now believes in subordination, exploitation, and separation from nature.

What’s the problem? We over-corrected. By whipsawing from dependence on the natural world to independence, we missed interdependence. As a direct result, the survival of our species and life on Earth as we know it is now in peril.

A few notes for the reader: I speak of the development of capitalism as an outgrowth of Western culture. I do not imply that Western culture is a monolithic culture nor that capitalism is a purely Western invention nor that the Western worldview is purely attributable to European roots. I understand that the West was and is highly influenced by all cultures with which it came into contact. There is no such thing as a purely Western worldview – we live in a fundamentally multi-cultural world. I focus on the “Western” worldview and its European roots because it is widely accepted that industrial capitalism is rooted in “Western” culture and European history despite its global presence in the modern world.

I use the term “humanity” frequently in reference to how the West viewed humanity. It’s not meant to claim truths about all humanity. I also make many references to the divine, god, and God. Each of these terms refers to the same essence.

The Arc of Western Ideology

The arc of Western ideology portrays an anxious creature trying to survive. At each twist and turn, we faithfully believe in, and even worship, the higher power that we think will help us survive (or save us from eternal damnation). It makes sense – humanity is a vulnerable creature in the natural kingdom. We’re slow, soft, weak flesh sacks without any fangs, claws, or poison to speak of. Our most powerful weapon is our intellect. With the mind, we create tools, build cities, hunt in groups, cultivate food, and defend ourselves.

In primordial times, we were heavily reliant on gifts from nature whether it be a favorable rainy season, a successful hunt, or a bountiful harvest. We worshipped the natural world personified in a pantheon of gods in part to exert influence over our surroundings.

Then, ancient Greek philosophers began to explore the potential of the human intellect to assert control over the natural world and those fickle gods. The West gradually unencumbered civilization from the power and unintelligibility of nature until, in the Christian era, humanity seized hegemony in the natural world from any higher power. In so doing, the West excommunicated nature and sequestered God to the abstract realm of spirituality. With the intellect liberated from external authority, we entered the modern era of industrial capitalism with no moral or cultural limitations on exploitation or consumption of the natural world.

Primordial Unity

We begin the arc of the modern Western worldview in the cradle of Western history: 8th century BC Greece. The Iliad and The Odyssey typify the ancient Greek ideology. Although attributed to Homer, the epic poems are widely concluded to be an amalgamation of popular stories passed on orally by travelling bards. They represent “a collective personification of the entire ancient Greek memory” (Tarnas, 1991, p. 17), a mythological canon from which all Western philosophy emanates.

Like many ancient cultures, the Greeks were animist: they believed that the natural world was very much alive, imbued with divine authority, and inextricably linked to the fate of humanity.

In the Homeric corpus, gods were indivisible from the natural forces that shaped the human world. Take for examples: Zeus, lord of the sky and thunder; Poseidon, lord of the sea and earthquakes; or nymphs, anthropomorphic personifications of nature, “daughters born of the springs and groves and the sacred rivers running down to open sea” (Homer, T. Fagles, 1996, p. 241).

The lives of gods and humans were also heavily intertwined. Poseidon developed a personal vendetta against Odysseus for his perceived arrogance and poking out his cyclops son Polyphemus’ eye. Athena proactively intervenes throughout Odysseus’ journey to shepherd him home. It seems like in every other scene a Greek sacrifices the thighs of a fatted goat to appease some discontented god and bring good fortune. It does not make sense why an all-powerful being should care about a feeble mortal’s hubris or the eye of one of his multitude of sons. The order takes form through the lens of a belief system that emphasizes the unity of humanity, nature, and the divine. Our fates are inseparable.

The First Wedge between Humanity and Nature

The ancient Greeks were highly inquisitive. Although they embodied animist beliefs, they also intellectually scrutinized the underlying truth of the world. In so doing, nature became an object of human consciousness, versus an extension of it, which surfaced a tension between the unification of humanity, nature, and the divine and the distinctly human capability of intellectual inquiry. This tension would form the backdrop for the next two millennia of philosophy until the Scientific and Industrial Revolutions. How can humans personalize the natural world if we can impersonally observe it? And how can nature be divine if the divine is omnipotent and unintelligible, but humanity can understand the natural world’s inner workings?

The locus of Greek philosophy sought to reconcile mythic belief and empirical rationality. Thales of Miletus, considered the first philosopher, accepted that “all is water, and the world is full of gods” (Tarnas, 1991, p. 19) while attributing impersonality to natural phenomena. Pythagoras sought to prove the divinely intelligent order of nature through mathematical inquiry. Socrates and Plato both restored nature’s divine standing and magnified the human intellect. Aristotle asserted both the world’s divine intelligent design and the human intellect’s power to comprehend it. The Stoics espoused a divine intelligent force permeating all nature – the Logos – that humanity can harmonize with through the intellect (Tarnas, 1991, pp. 21-76).

More radical philosophers proposed ideologies that completely stripped nature of cosmic significance, diminished it to mere atoms operating according to mechanical laws and impelled by pure chance. Mythic systems held no epistemological value – only intellectual inquiry and empirical facts can yield knowledge. Maybe the gods don’t even exist.¹

Greek philosophers first hypothesized a fundamental separation between humanity and nature. Nature and the divine were still unified, but humanity was uniquely capable of comprehending both.

* See Leucippus and Democritus’ atomism, Sophist skepticism, and the teachings of Epicurus.

The Incarnation of God in Humanity

With the conversion of Roman Emperor Constantine in the 4th Century AD, Christianity decisively seized the throne of Western philosophy. Christianity shared the belief in a divine order to nature, characterized by the Greek Logos, with the Judaeo-Christian spin of chosen people and fulfillment of a salvation prophecy through Christ.

Most importantly for this essay, Christianity decisively incarnated divine intelligence in humanity. “In Christ, the [Greek] Logos became man… the human and the divine became one” (Tarnas, 1991, p. 102). By fundamentally linking humanity with the divine and severing the natural world’s connection, Christian doctrine squeezed the spiritual significance out of the natural world into the human experience. Humanity could now completely circumvent the natural world to commune with the divine. Even more extreme, the natural world became something to “overcome for spiritual purity” (Tarnas, 1991, p. 139).

Early Christian tradition excommunicated nature by fusing the human mind and the divine. Without a recognition of divinity in nature, the West lost the sense of unity, reverence, and respect that bound us to the wellbeing of the natural world.

Intellectual Liberation

With Christianity firmly entrenched as the dominant philosophy in the West, the Church loosened its autocratic hold on independent thought. In the 12th and 13th centuries, the Scholastics, culminating with the works of Thomas Aquinas, re-imbued the natural world with divine significance while encouraging intellectual inquiry. In the Greek tradition, the Scholastics attempted to reconcile mythic belief and empirical rationality by affirming the divine intelligence of the natural world (Tarnas, 1991).

Unfortunately for the Church, the re-invigoration of intellectual inquiry exposed incompatibilities between Christian doctrine and empirical rationality. In order to maintain Church authority, William Ockham proposed the complete separation of the divine from the material world (Tarnas, 1991).

Logical reasoning applied to the material world of nature while faithful belief applied to the immaterial realm of spirituality. It followed that Church and State, the religious and the political, must be separated to preserve the free pursuit of knowledge and sacrosanctity of Christian doctrine (Tarnas, 1991, pp. 206-208). Now, God was disconnected from both nature and the human intellect.

With the intellect liberated from any higher power in the material world, a wave of humanistic, individualistic movements swept Europe. The Renaissance exhorted a human-centric worldview, the Reformation asserted the ability of the individual to commune with God directly, and the Scientific Revolution unleashed empirical rationality on the natural world. (Tarnas, 1991). The wedge between humanity, nature, and the divine first hammered by the ancient Greeks was now a chasm. Reconciliation of mythic belief and empirical rationality became a divorce.

Thus formed the foundation of modern industrial capitalism. Humanity: autonomous and isolated, liberated from any higher power or authority in the material world, uniquely capable of penetrating nature’s secrets, supreme by virtue of the intellect. Nature: devoid of cosmic significance, governed by mechanistic laws, a playground for humanity. God: no longer omnipotent, the material world no longer its domain, sequestered to the abstract realm of spirituality.

The Problem with Industrial Capitalist Beliefs

In the industrial capitalist belief system, humanity is free to use and consume the natural world with our powerful technologies as we alone decide. Unfortunately, humanity’s moral and cultural values have not kept pace with scientific and technological advances. Despite the West’s remarkable accomplishments and ingenuity, we have failed to recognize our fundamental interdependence with the natural world.

Planetary scientists know that atmospheric carbon is higher than any point in the last two million years from human activity (Grinspoon, 2016). Ecologists know that we are conclusively in Earth’s sixth mass extinction event with wildlife populations down 69% in just 50 years (World Wildlife Fund, 2022 Living Planets Report). And economists project mass forced migration due to climate change. The climate crisis emphatically shows us that we are subject to the same natural powers as other life forms. We cannot survive without the energy and nutrients that the Earth and the cosmos provide – we just think we can because the average person is highly disconnected from the natural resources required to grow their food, fill their bathtub, power their home, or fuel their car. Technology enables us to be more efficient with our natural resource use and design renewable resource systems, which are excellent innovations. However, our entire livelihood is fundamentally dependent on the Earth’s provisions because we are organic life forms! All the technology in the world will not save us if we destroy the food, water, and energy that all technology depends on. So, who is really the higher power? We confused intelligibility and interdependence for inferiority and independence.

Ultimately, the Earth will be fine. Our actions do not destroy the Earth so much as destroy humanity’s ability to live on it. The history of the Earth, a lot longer than the history of humanity, shows that new ecosystems and new life forms will develop after a catastrophic extinction event. The real question is whether we want to be a part of the future.

Humanism, empirical rationality, science, technology, and capitalism are not the enemy. I do not romanticize pre-industrial life. Industrialization, science, and technology yielded massive benefits in quality of life and life expectancy. I had 3 teeth knocked out and shattered my jaw, but modern medical professionals reconstructed me. The market economy guides behavior change on a global scale without centralized authority. I can board a metal tube with 300 strangers, fly through the atmosphere at almost the speed of sound, and be on the other side of the planet in a matter of hours. All these innovations were unbelievable just a handful of generations ago.

However, they are not absolute truths or worthy of deification. They are tools for survival. We projected a fundamental need to faithfully believe in a higher power on to science and technology. It knows all, explains all, and controls all. That sounds a lot like the omniscient and omnipotent God that technocrats deride. Do we really have a separation of Church and State? It is time to put technology into its rightful, dignified place as a means, not an end.

Most importantly, this ideology cannot sustain human life going forward. If we want to ensure our survival, we need a new paradigm.

Final Thoughts

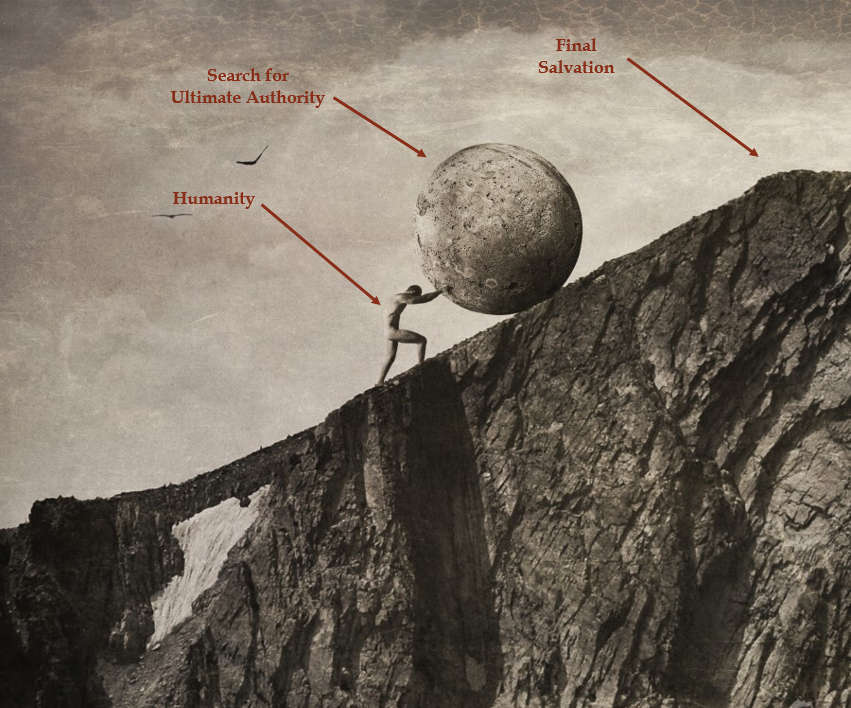

The narrative of Western ideology depicts the Sisyphean task of seeking a higher power, an ultimate authority that will ensure our survival. Throughout history, we think we finally figured it out, then we are inevitably wrong. Industrial capitalism is already coming apart at the seams. Einstein’s theory of relativity and quantum mechanics break the laws of Newtonian physics. It is becoming clear that extractive industrialization is not compatible with sustaining human life on Earth.

Tectonic ideological shifts occur when the prior worldview fails to satisfy this human anxiety for survival. I think we are on the precipice of a global transformation to a post-industrial capitalist ideology as climatic catastrophes occur with alarming frequency. I hope we move towards a worldview that accepts the Earth as the higher power. It does not rely on eco-spiritual faith. We only need to accept our dependence on a healthy biosphere and our power to both nurture it and destroy it.

Source Material

Davis, Wade. (2009). The Wayfinders: Why Ancient Wisdom Matters in the Modern World. House of Anansi Press Inc.

Grinspoon, David. (2016). Earth in Human Hands: Shaping Our Planet’s Future. Grand Central Publishing.

Homer. (1996). The Odyssey (T. Fagles, Robert). Penguin Group.

Tarnas, Richard. (1991). The Passion of the Western Mind: Understanding the Ideas That Have Shaped Our World View. Ballantine Books, The Random House Publishing Group.

World Wildlife Fund. (2022, October 13). WWF Living Planet Report: Devastating 69% drop in wildlife populations since 1970. https://www.wwf.eu/?7780966/WWF-Living-Planet-Report-Devastating-69-drop-in-wildlife-populations-since-1970.